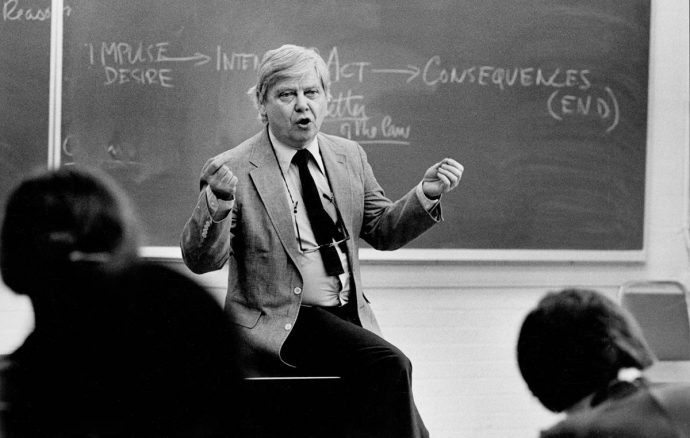

It was my privilege to participate in a tribute to William Gass at the 2009 AWP conference in Chicago. The following is a transcript of my attempt to honor the immensity of his gift to us all; he was and still is the great animating spirit of his university, Washington University in St. Louis. Please note that everything in italics—that is, the language that takes your breath away—is his.

Gas up, gas light, gas mask, gas chamber. Step on the gas! It’s a gas. Gas bagging, gas pump. Bubber gassed me, says Duke Ellington of the trumpet’s wa wa sound on East St. Louis Toodle-oo. He has been laid on here like the gas all during the Christmas, says Aunt Kate of Mr. Browne lurking at the door, laughing as if his heart would break. Jazz it up, keep moving! She is come at last . . . at last . . . and all is gas and gaiters! says the old gentleman who tumbles down the chimney into Mrs. Nickleby’s bedchamber clad only in small clothes and gray worsted stockings. You might lose it you know. You are inclined to lose things, Paula, says Charles Boyer, of the heirloom brooch he’s already snuck from her purse, gaslighting Ingrid Bergman. The pitcher, when he’s really hot (a gashouser like Dizzy Dean of the ‘34 Cardinals), is said to be throwing gas, the ball so fast or slow or knuckled or on such a mysterious, elusive trajectory as to be untouchable, hurtling “backwards and forwards, down and up, through both the ends of the telescope” as James Joyce says in “Gas from a Burner,” or Alice tumbling down that tunnel of a rabbit hole past cupboards and book-filled bookshelves and how many times have I fallen inside a sentence while running from a word? Winckelmann, Kafka, Kleist. Within the rhythms of reason . . . the withheld breath, the algebra of alliteration, the freedom of design . . . James and James and James the Joyce . . . So the sentence, in search of its birth, is passing through the company of writers the writer has stored like so many bars of soap, barrels of pickles, sacks of coffee, candles connected by uncut wicks. It wants a rhythm the way infants need feet; it hopes for a satisfactory rhetorical shape; it curses its bad luck and low-class diction; it likes to hum a tune as it rolls along . . . You’re a gas, you’re the noble gasses, you’re a gas, like The Golden Ass is, I’m an undigested bit of beef, alas, but if baby I’m ignoble, you’re the Gass. Such a round, ripe seedful name cannot be invented, a name meant for amusement and one which, even in German, means “alley.” Though [he is], Gassy was not the worst [he] was called.

Among the derivations of the word I especially like the Greek chaos—suggested by Paracelsus’s use of chaos or gas for the proper element of those spirits adept at moving through solid earth as fish move through water, as the writer’s imagination moves through the world, here displacing snow—a blue-white cave, the blue darkening. Then tunnels off of it like the branches of trees. And fine rooms. In and in. Stairs. Wide tall stairs. And balconies. Windows of ice and sweet green light—or there digging through clay, dirt in the eyes, under the lid, against the ball, against eyewhite and iris . . . pushing a few shavings of the clay back . . . everything claustrophobically close, so stifling not merely to the nose but to the spirit . . . Both the hollow that’s taken out of language in order to somehow get through it and also the place to which [you] come every day and dispense of the words [you’ve] dug up.

The sixteenth century Dutch chemist J.B. Van Helmont supposed Gas to be an occult principle contained in all bodies, invisible, ineluctable, “a far more subtile or fine thing than a vapour, mist or distilled oylinesses, a Spirit that will not coagulate, or the Spirit of Life, a Balsom preserving the body from Corruption,” though far from preserving the body it can also signal its corruption, “the sweet smell of gas-gangrene from a rotting leg”—each work simply the first paragraph rewritten, swollen with sometimes years of scrutiny around that initial verbal wound. Gas is a mode of existence, said a doctor named Kerr in the eighteenth century. According to contemporary physics, gas is a state of matter, consisting of a collection of particles, molecules, atoms, electrons, without a definite shape or volume that are in more or less random motion. The quiet spiral of the shell, a gyre, even a whirlwind, a tunnel towering in the air: these are the appropriate forms, the rightful shapes; yet the reader must not succumb to the temptations of simple location, but experience in the rising, turning line the wider view, like a sailplane circling through a thermal, and sense at the same time a corkscrewing descent into the subject, a progressive deepening around the reading eye, a penetration of the particular . . . at once escape and entry, an inside pulled out and an outside pressed in . . .

When we breathe, we take in the oxygen we need to live, but we also acquire at the same time the air necessary to form words, and these are sent forth, when we exhale, in the same way that the lion growls or the hyena chortles. The air we breathe is gas, as is the air that escapes us. When it begins life in the kitchen things which were formerly perceived and named as nouns cook down into their adjectives: gas range, gas grill, gas mark, agents in the preparation of the foods we eat that travel down that other tunnel, becoming no longer ineluctable but eructable, gas burner, gas oven, gas flame, gas blue. The blue flame of the gas jet and the jet’s diminutive pilot tucked away under the stove top, the author in his study as absent as last year, as distant as Caesar cooking something up—really cooking with gas now, the sentence, seeking its form, must pass through belly and bowel without irritation, as though it belonged in that dim hallway, as though it was—as though it were—on skis, on rails, on call, on a mission.

Gas, oh gas! So exhilarating, so deadly! Never one thing without being the Other, the man at the table calmly spoon[ing] oatmeal into his mouth while words pass woundlessly through his eyes, divid[ing] more noisily than chewing, becom[ing] a Gulf, a Red Sea none shall pass over, dry-shod cross. There is no miracle more menacing than that one. As crucial to life as the air we breathe, Gas, but also as dangerous to the complacent lives we’d like to live. Invisible to the naked eye, the material that makes up a story must be placed under terrible compression, but it cannot simply release its meaning like a joke does, silent but deadly like flatulence, or the gob gas so pernicious to the respiratory systems of canaries in coal mines, what seeps from imperfectly closed gas cocks, or else escapes with a hiss, “a new kind of inflammable gas which can be made in a moment without apparatus, and is fit for explosion.” The gas oven, good for baking bread or sticking your head into. Gas bomb, gas mask, gas chamber—the cruelest and most artful devices our civilization has devised . . . The Boche took out the teeth because they were the bones that bite, that inform, that dream; and which bone, indeed, do we dream with if not the dream bone? Yes, the bone which Moses blew to dream the Lord. No gold-filled molar has a majesty to match it. Dice made of dream-bones rattle in the dice box, throw down a pair of tyrants shaped as double dots; cast Christ’s lot; toss out a series of sevens or those boxcars Jews were packed in.

Gas is able to inhabit the tiniest particle of matter, whether terrible or marvelous, the incinerated body flaking into ash or each ash flake the gas lantern’s mantle turns to, incandescent, each glistening fleck of gas black pigment in Max Beckmann’s terrifying triptychs, the bubble rising up the glass gauge of the gas pump pumping full the gas guzzler, the gas harmonicum’s impossibly high impossibly beautiful note, capable of scaring small animals to death. Impossibly small, invisibly small, and then, impossibly huge, the solid burning bodies of the sun and stars sending their light through burning gas-laden atmospheres, that place where the gas giants rotate on their immense axes, Jupiter and Saturn and Neptune.

We listen to writers who have written well—wondrously well—because that self through which the sentence passes—those eyes, those ears, that nose—is made not of flesh and bone and their dinky experiences, but of pages absorbed from the masters . . . Gas Giant: the great planet containing everything, real gas, ideal gas, perfect gas, laughing gas . . . a pure gust of forthcoming, as Rilke might have written—a perception, a presence a force . . . sucked up from Indiana the way Dorothy was inhaled from Kansas and placed [high above the pole] to see below the rocking gray water and great herds of icebergs seeking their death down the roll of the globe.

The ending will be, of course, unsatisfactory, as it will end in the imagination, not in the fact, as if the imagination had filled the gaps between facts with more facts, whereas only fancies are there. All stories ought to end unsatisfactorily.

At the quick edge of space . . .

Kathryn Davis is the author of seven novels, the most recent of which is Duplex (2013). Her other books are Labrador (1988), The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf (1993), Hell: A Novel (1998), The Walking Tour (1999), Versailles (2002), and The Thin Place (2006). She has received a Kafka Prize for fiction by an American woman, the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 2006, she won the Lannan Foundation Literary Award. She is the senior fiction writer on the faculty of The Writing Program at Washington University.